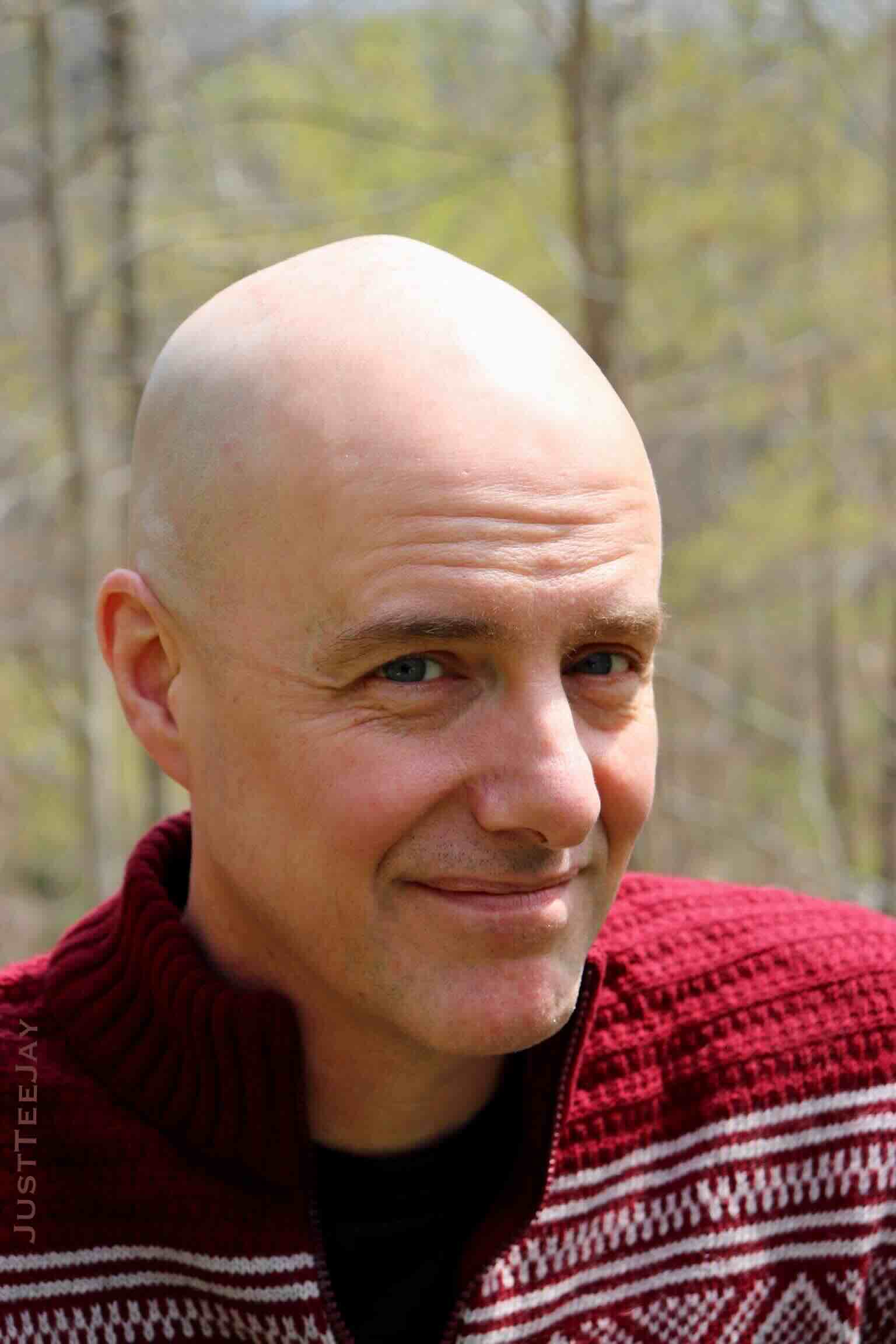

Taormina Film Festival, meeting with Martin Scorsese: 'Seeking the truth'

Check out the meeting with Martin Scorsese: movies, plot

At the

Taormina Film Festival, we met Martin Scorsese, who received the Lifetime

Achievement Award.

You’re

working on a project about Jesus set in the contemporary world. Can you tell us

more about it?

"I

think it will take me more time, probably until next year, before finalizing

it. This idea dates back to the early '60s, when I wanted to make a film based

on the gospels but set in New York’s Lower East Side, in the tenements and

slums where I grew up. I had planned everything. But at that time I was just

starting out, involved with NYU, which was very small then with only 30

students. Now there are thousands in the film department.

I was

thinking about these ideas, we wanted to shoot in black and white, obviously.

Then I saw Pasolini’s ‘The Gospel According to St. Matthew’ and had to find

another approach, which years later became ‘The Last Temptation of Christ.’ From

there it evolved through ‘Kundun’ and finally ‘Silence.’ It’s still an ongoing

search, and it’s what I’m trying to do in the time I have left. I’d like to

create another approach to this theme and I found Shusaku Endo’s book on the

life of Jesus interesting. I

might base it on that, with modifications. It’s just a matter of another six

months or so to figure out how to proceed."

Meanwhile,

you’ve worked on a series about saints, ‘The Saints.’

“It was

also shot in Italy. Last year filming took place in Morocco too. It’s produced

and created by Matt Madden. I present it and Kent Jones is writing all the

screenplays. The characters include St. Paul, St. Peter, Mary, and St. Patrick,

among others. They’re films of less than an hour that are then discussed by a

panel including Father James Martin, a Jesuit who was our consultant for

‘Silence,’ Paul Elie, Mary Karr, and others. We discuss all these different

aspects and so far the first season has gone very well, so we’re shooting the

second.”

You’ve

had the opportunity to meet Pope Francis.

“Yes, I’ve

met him several times. We’re preparing a film titled ‘The Schoolboys’ that’s

set in Argentina. The film was shot in Sicily and Gambia, and it’s a

true story. I’m connecting with other cultures, other ways of thinking, and I’m

learning a lot. I believe this stemmed from the documentary made with Pope

Francis about elderly refugees. I was among the youngest of the ‘old ones’ in

that project, made a few years ago for Netflix.”

How much has religion influenced your personal and

artistic development?

"One of the places where I found a kind of refuge was

the downtown cathedral. There was a priest who was very good with us young

people, very passionate. He introduced us to literature, to James Joyce and

other authors, and also to films. He offered us a very different approach from

how we were living in the old world. We were a new generation, different from

those who arrived in 1900 or 1910: there was another world out there called New

York, which was part of a place called America, which in turn was part of the

world. He talked to us about both realities and for the first time I thought it

would be wonderful to be like him, to be a teacher.

But I was always sick, I had terrible asthma, I didn’t play

sports and always spent time at the cinema or in church. For me, there was no

way to follow that path. I lasted only about six months in that small seminary.

I also understood that vocation is a calling, so the call must be stronger than

simply wanting to be like someone. You really have to understand who you are,

it’s not about yourself but others, and I simply couldn’t do it. At the same

time, cinema, films, and storytelling were always present and somehow I slipped

into that world."

How does this religious background manifest in your

films?

“Religion and spirituality are different things. You’re in a

world of sin and you’re expected to atone for your sins simply by going into a

building and praying for an hour. And I wonder, ‘how do you do that?’ We go in

there, okay, we come out, there are people, money, weapons… I mean, there was

organized crime. And regular people, those who had a grocery store, were

oppressed by these criminal groups. They were good people. So the religious

aspects are always present in my films, like in ‘Taxi Driver’ and ‘Raging

Bull.’ The stories I was attracted to – and the characters – always seemed to

have, sometimes unintentionally, a sort of Christian background and a search

for spiritual peace with themselves.”

In your films, you’ve often portrayed New York and its

social dynamics. How do you see the evolution of the city and America in

general?

“New York is my neighborhood, it’s where I grew up. I could

walk around and see all these buildings, bright places, the underground markets

where you had to go in and kill the chicken in front of them. And the cemetery.

All this was real, so setting stories there was natural. The only thing is that

there weren’t Italians but Irish. Irish immigrants were the first to face the

attack on immigration. This is the story of America, and America’s roots have

always been deeply marked by blood.”

The current situation of immigrants in the United States

seems to be repeating itself.

"It always repeats. For Italians there was a quota.

Many Italians came from New Orleans and other areas, but the point is that any

new group that comes to experience democracy is opposed because it’s different.

Hence the value of the story we’re trying to tell with the film for Francis, to

understand how much everything has changed.

If I got in a car now, I would only know certain streets,

everything else has changed. What was paid dearly by the Irish, who then

settled and after a generation or two managed to run politics and law

enforcement. The Italians were outsiders, and after the Italians, I remember –

growing up in Manhattan – there were Puerto Ricans: hence West Side Story.

Every new group that arrives, Asian or other, must go through a kind of

conflict process before there can be assimilation, because the nature of the

country is to continuously introduce new cultures. So every culture will

experience conflicts. It might be Pakistan, India… You have to learn to

assimilate somehow in America. The experiment of democracy is under stress, but

reading much of history, it seems it has always been so."

Do you see parallels with the current political situation

in the United States?

"It’s close to the American Civil War of 1860, as the

division in the country is so clear. I was in Oklahoma and had issues there.

We’re politically very different, but we had a good time together. It’s a very

interesting thing, but unfortunately tragically divided. It will take a

generation, hopefully just one generation, for it to become a bit more

comfortable. I don’t think that in the end, when you have so many different

cultures and people with different ways of thinking, there will always be the

possibility of difficulties.

I find that this administration under Trump takes pleasure

in working against people. And with new technology, of course, one no longer

knows if truth exists. At first I thought, well, this is really the end of

democracy, it’s about to be tested. No matter what their intentions are, some

might be good, I don’t know, I don’t have the qualifications to say, but their

style for me is the opposite of what I would direct myself toward. It’s anger

and hate.

Two things are happening: one is the verification of the

president’s power, and this will have serious repercussions for future

generations. It’s not just a president who wants what he wants. How much power

can they have? The other thing is how long the American public, the voters,

will endure. What happens if some of these policies, which I don’t understand –

I don’t understand tariffs, for example – if someone realizes that this will

cost them a lot of money for a long time? I believe these are the two factors:

people need to be strong enough to work at least to control the president’s

power, and how long the public can bear if these programs don’t work."

A final question: what can cinema do in this delicate

moment?

“The fundamental thing is to continue seeking the truth. The

truth might be different across the street, but it’s your truth. You might not

agree with certain things, but how do we know what’s true? That’s the problem.”

© All rights reserved

You Might Be Interested

I Can Only Imagine 2, Milo Ventimiglia interview

The statements of Milo Ventimiglia

I Can Only Imagine 2, Sophie Skelton interview

The statements of Sophie Skelton

Return to Silent Hill, Eve Macklin Interview

The Strangers Chapter 3, Madelaine Petsch Interview

The statements of Madelaine Petsch

In His Wake, Chad Zunker interview

"Family secrets are the centerpiece of my new novel"

Tell Me Softly - Dímelo Bajito, Lilliana Cabal interview

Amazon Prime original based on Dímelo Bajito

New novel After the Fall, Edward Ashton interview

By the author of Mickey7

Send Help, Sam Raimi Director and Zainab Azizi Producer interview