Interview with Laura Nikolov, Producer of Spring Came on Laughing and From Ground Zero

Also producer of Spring Came on Laughing

The latest film she chose to produce, Spring Came on Laughing, directed by Noha Adel and presented at the Cairo International Film Festival, shows women with their treasure chests of emotions in different existences. What made you decide to produce this story?

What made me decide to produce this film was, above all, its originality. I found it to be a unique and subtle way of portraying the lives of Egyptian women, regardless of their social status. The idea of telling this story as a springtime tale particularly resonated with me. For me, spring symbolises a period ripe for revolutions, as history has often shown us. In this film, that season becomes the stage for an outburst — a release of built-up social, societal, and economic pressures. I loved the perspective it offered, the freshness of the narrative, and the fact that it addresses serious subjects with a touch of humour. Even when these women reach a breaking point, I find it is portrayed with compassion and humanity. They are so strong. They have absorbed so much over the years, and their 'breaking point' is a legitimate way of saying, 'enough is enough.' I was also touched by the way these women were filmed — they are immensely beautiful in their strength, fragility, and truth. This deeply moved me and reinforced my desire to support this project.

Spring Came on Laughing premiered at the Cairo International Film Festival and was also shown in Italy. What message or experience does this new production of yours convey?

Yes, the film premiered in its country of production, at the Cairo International Film Festival, where it was very well received by the audience. The premiere was completely sold out. However, to my knowledge, the film has not yet been screened in Italy. As for the message or experience this new production conveys, I see several things. Firstly, the fact that an Egyptian woman director picked up a camera and, with a predominantly female team, chose to tell stories about women. What’s also remarkable is that no professional actors were involved in the film; the cast consisted of friends, family, colleagues, and acquaintances of the director and producer. For me, this is something fundamental. I believe this film represents a beautiful production experience because it tells a story that everyone involved was eager to share. It’s a process I find both beautiful and respectful, and I hope audiences everywhere will connect with what these individuals have expressed. Finally, I think this film is an attempt to refresh the way we talk about these kinds of subjects. It’s a form of experimentation that excites me, and I want to continue exploring it — not only with Noha Adel in her future films, but also alongside Kawthar Younis. I believe we make a strong team, and I want to apply this fresh and sincere approach to my other film choices and projects.

You produced Ground Zero. Can you tell an anecdote from behind the scenes, the experience of producing the film, the crew, the cast, do you have a memory to share with the audience?

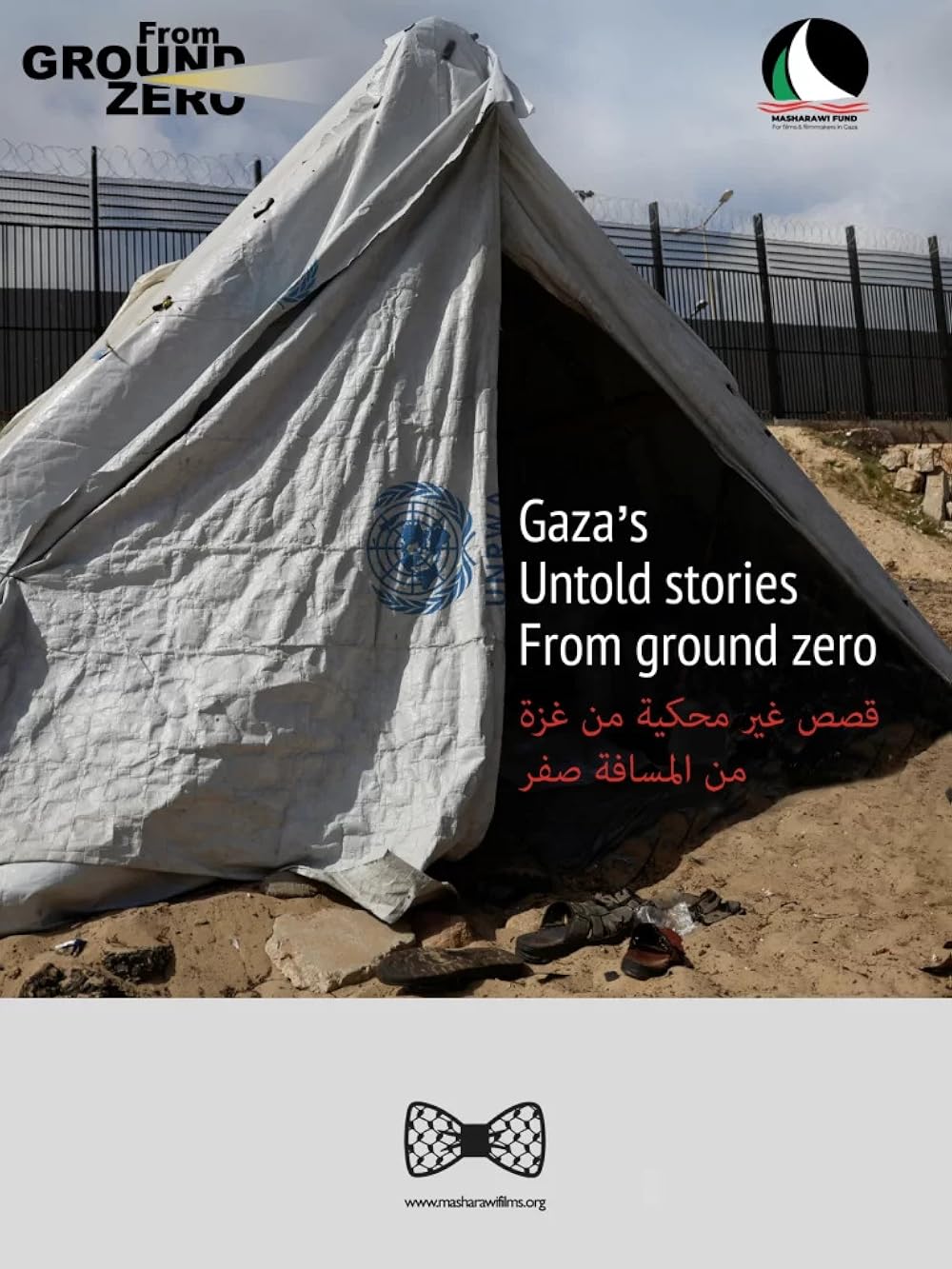

Regarding *From Ground Zero*, it’s a completely different project, as it’s a collection of 22 short films shot in Gaza between January and June 2024. This project was initiated by the Palestinian director from Gaza, Rashid Masharawi. Naturally, given the war and the fact that no one could enter or leave Gaza, it was a more than unique experience. For me, it was a relationship entirely built remotely with the team on site, which made this production truly exceptional. I don’t want to use the word 'difficult' because the people on the ground are the ones experiencing truly challenging realities. From my position in Rennes (France), my role was mainly to adapt our usual filmmaking processes — from development to distribution — so they could work despite the circumstances.

This meant rethinking traditional steps entirely, as the urgency to film, tell stories, and share these messages didn’t allow for a conventional process. We had to do everything simultaneously: development, production, shooting, and post-production. It’s a project that mobilised incredible people, both in Gaza and beyond, who believed in this venture and supported it. Today, this film is travelling the world and has been selected to represent Palestine at the Oscars. It’s an incredible story. Thanks to this project, we not only managed to amplify the voices of the people of Gaza but also gave them the opportunity to tell their own stories. Their narratives, told by those living these realities daily, are very different from those of journalists or outsiders.

In terms of behind-the-scenes anecdotes, there are countless ones. I think of the sleepless nights waiting for the rushes to download or the hours of anxiety when the internet suddenly went out, leaving us without news from the team. Thankfully, today, all our team members are alive, although each of them has faced immense losses — family, homes, and more. I can’t say they’re doing well because every time I see them on video calls, they seem visibly thinner and deeply marked by their experiences. But they are here, and that’s already a relief.

The film has been selected by Palestine to compete for the Oscars. Can art open the eyes of a nation's society?

That’s an excellent question. If I’ve committed myself to this project, as with others, it’s because I deeply believe in the power of art. I think this film will resonate differently with various audiences: those who already know the history of the region, but also those who knew vaguely about it without being fully informed. The reception will inevitably vary depending on the viewer. What struck me most about the process was that we gave no conceptual directives to the directors on site. They chose their subjects and approaches themselves, and we simply provided assistance through a team of artistic advisors to help them express what they wanted to say. There was no censorship of the topics chosen. The only thing we ensured was that there were no repetitions in themes or approaches and that the films were feasible under the safest possible conditions.

What’s astonishing is that, without any imposed conceptual framework, we ended up with 22 short films that all celebrate life, hope, and the desire to keep going and believe in a better future. There isn’t a single word of hate in these films. Instead, they oppose the often oversimplified, black-and-white narratives created during conflicts. This film brings much-needed nuance, which I think is vital right now. I believe art can build bridges between cultures, especially in times of war when people cannot physically travel to these places. Art allows us to understand another person’s reality, to humanise them. It doesn’t mean we can fully put ourselves in their shoes, but it helps us imagine their daily lives and bring their stories closer to us. In this sense, I think this project is a success.

And finally, one more thing about art: I believe that with this project, I’ve experienced something fundamental. What makes us human is our ability to create. Because when our daily lives are reduced or restricted to simply fighting for basic needs, it is the creative process that adds an essential dimension to our existence. It’s what makes us profoundly human, as it elevates us beyond mere survival.

And this, I believe, is an important lesson that these directors taught me by seeing their work through to the end.

Coming back to Spring Came, the director of the film explained how the individual stories that intertwine in the plot are inspired by Egyptian poetry, Egyptian music, and the beauty of Egyptian landscapes. How do you see this as representative of a culture that is thousands of years old?

I believe we are all the result of cultures that span thousands of years. It’s impossible to trace all the migrations and transformations our distant ancestors experienced. For that matter, I’m not sure many families know precisely where they come from. As for me, I know I’m a mix of eclectic Eurasian heritage. But I couldn’t say exactly what my culture is made of in its entirety. Like anyone on this planet, I am the heir to millennia of diverse and varied cultures. That said, I don’t think Noha Adel aimed to comprehensively represent all of Egyptian culture in her film. Her approach was more about drawing from specific elements, such as poetry, music, and landscapes, to enrich the stories she wanted to tell. For a more in-depth answer, I think it would be interesting to explore this question directly with her, as it’s primarily her vision that comes through in the film.

© All rights reserved

You Might Be Interested

Donna Reed: From Hollywood’s Golden Age to Television Pioneer

Donna Reed born in Denison on January 27, 1921

Paul Newman: A Historic Legacy

Paul Newman was born on January 26, 1925, in Shaker Heights, Ohio

How to Make a Killing, Stevel Marc interview

How to Make a Killing will be released in theaters on February 20, 2026.

Send Help, Sam Raimi interview

The statements by Sam Raimi

Send Help, Rachel McAddams interview

The statements by Rachel McAddams

Ponies, Haley Lu Richardson interview

the statements of Haley Lu Richardson

Ponies, Emilia Clarke interview

The statements of Emilia Clarke

The Strangers: Chapter 3, Madelaine Petsch interview

The comments from Madelaine Petsch